By Karen Yvonne Hamilton, 2023

How do we tell the truth in personal writing (memoir)?

When my husband was dying, he said to me, “Where do all the stories go when a man dies?” He was in and out of consciousness at the time, so this one question hit me like a bolt of lightning. Alex was a man of stories. People of all ages loved to hear his tales of an adventurous life travelling the country during the 1960s. His stories did not die, will not die. He wrote them all down in a memoir titled The Brooklyn Hobo. He always said that writing that memoir brought him such peace. How can we bring that peace to others? Novelist Philip Pullman remarks on storytelling by saying, “After nourishment, shelter and companionship, stories are the thing that we need most in the world” (Underkofler et al., 2020, p. 77).

“After nourishment, shelter and companionship, stories are the thing that we need most in the world.”

(Underkofler et al., 2020, p. 77).

My passion in life is getting people to tell their stories. Many people are excited about doing so, but they claim they have no time, or they are not writers, or they are afraid to tell the truth. So, it has become my task to convince people of the power of words to heal, the power of stories to affect change in themselves and others, and the power of storytelling to add to the collective history of all mankind.

When talking to others about writing a memoir, the question always comes up: How do I tell the truth? And further, how do I know if what I remember IS truth? So, how do we tackle the issue of what constitutes truth in a memoir?

Definitions

First, we need to define autobiography, memoir, and personal history.

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines autobiography as “An account of a person’s life given by himself or herself, especially one published in book form” (OED, 2023). So, the autobiography is an account of a whole life.

MEMOIR

Interestingly, the OED defines memoir simply as “A biography or autobiography; a biographical notice” (OED, 2023). While the Autobiography typically takes a linear narrative form, the modern Memoir takes a shorter form (de Bres, 2021). We have come to define a memoir in modern terms as more of a personal essay that ruminates on a single event in a person’s life.

PERSONAL HISTORY

A personal history is more historical in nature, taking a historical event that the writer has personally experienced and recounting that experience living through that event. Personal histories are often woven into larger narratives such as a family history which recounts the stories of a writer’s ancestors. This type of writing takes the autobiographical writer and positions them more in the outer world rather than just subjective thoughts and feelings. It requires that the writer show their reactions to the historical event.

What are we writing?

So, we ask ourselves: Are we writing an account of our full life, are we writing an account of one part of a life, or are we writing an account of a larger event positioned within historical events? If an autobiography is an account of all of the experiences in one’s life, then a memoir is an account of just one of those experiences. Experiences are naturally subjective to time and are subject to revision and therefore could be construed as fiction. The question still being debated is whether or not memoir as a genre is categorized as fiction or nonfiction. Van de Pol says in her thesis, “Truth in Autobiography”, that her “memoir/novel” is a “fragment of a story” (van de Pol, 2013). She writes about the working class in Melbourne, Australia, but more importantly, she writes about how she experienced growing up in this working-class community. Her memoir reads as a personal history because she becomes an active participant in history itself.

Subjectivity

A field of writing called autoethnography focuses on the cultural context of a personal experience (Karalis et al., 2023). This field delves into the inherent connection of society and the individual. It welcomes the subjectivity of the personal history writer because it recognizes that the very subjectivity that others use to question the author’s authorial voice is the exact characteristic that brings validity to the personal experience. One person’s subjectivity provides a human connection to the retelling of a historical period of time. We move past dates and times, and ‘hear’ the human experience, the perspective of one person’s recounting of history.

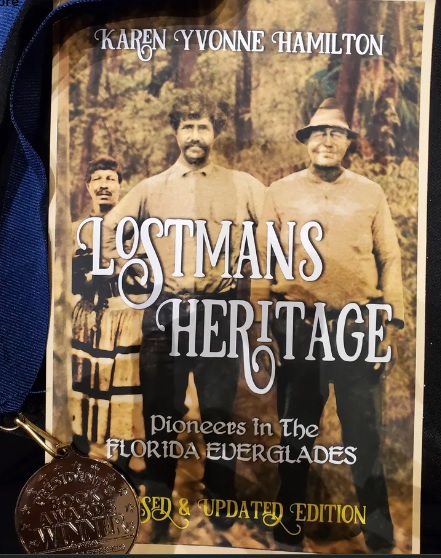

In my own personal narrative, Lostmans Heritage: Pioneers in the Florida Everglades, I grappled with the truth on many occasions. I had a major university press interested in publishing the book. After months of working with them, my editor said, “We need you to remove your story. Our press has to decided to go with only objective historical narratives.”

My book included not just history but also the narration of my thoughts and feelings as I researched and uncovered mysteries and secrets of my pioneer family.

I told her, “I don’t want to write a non-fiction narrative removed from my own personal journey. My journey is half of the story!”

I ended up self-publishing the book and have received many review from readers who say the true personal story is what they loved the most. I addressed the problematic arena of truth by beginning the narrative with a disclaimer of sorts,

“At best we are able to find facts and statistics that recreate a general foundation to build on. I find the older the source, even news articles, the more trustworthy the information is. I won’t say that I trust every news article that I read, but these at least give me something to start with other than family lore. Tales passed down through the generations tend to be biased, exaggerated, or both, like the classic game of ‘telephone.’ Still, in the end, all that we can do is imagine the rest, fill in the missing pieces with generalities that might have occurred. English historian G. Kitson Clark (Novick, 1988) once said that these generalizations are “necessarily founded on guesses, guesses informed by much general reading and relevant knowledge, guesses shaped by much brooding on the matter in hand, but on guesses nonetheless”

(Hamilton, 2019).

Talk Story

Like my book, other writers have woven their personal stories (and those of their ancestors) into narrative novels that follow the story format. When telling the stories of the ancestors, writers work to find a way to relate the generational lore and cultural backgrounds of a past which they have little personal recollection. Does this form of personal narrative invalidate the authorial voice? Can an autobiographical writer tell someone else’s story?

Maxine Hong Kingston tells the stories of her ancestors in her novel, Woman Warrior. Inherent in the idea of autobiography is that the text should provide its readers with descriptions of time and place. The largest objection to Kingston’s novel is that readers who are not Chinese read the text and take Hong’s words as factual accounts of Chinese culture. Chinese readers have objected to the way in which Chinese culture is portrayed in Woman Warrior.

“Woman Warrior actually violates the popular definition of autobiography — a chronologically sequenced account with verifiable references to people, places, and events”

(Wong, 1999).

This is only the case if one uses that definition of autobiography. Jean Starobinsky, in an article titled “The Style of Autobiography” comments that “Every autobiography—even when it limits itself to pure narrative—is a self-interpretation” (Starobinsky, 1990). Woman Warrior in actuality presents a sequence of the author’s self-interpretation in time. Kingston’s narrative is based on what she calls ‘talk-story’ and she weaves the stories told to her as a child by her mother into an autobiographical text. In essence, she is handing down to future generations the ‘talk-story’ and the question of what is truth becomes irrelevant. The autobiographical tale that she tells is her tale.

At the conclusion of “No Name Woman”, Kingston tells the reader, “My aunt haunts me—her ghost drawn to me because now, after fifty years of neglect, I alone devote pages of paper to her…” (Kingston, 2001, p. 315). Kingston not only attempts to recreate her past, but the past of her ancestors as well. “…every telling or retelling of a story…is a new telling that encapsulates and expands upon the previous telling” (White & Epston, 1990, p. 13). What the reader assumes to be factual is not relevant to Kingston, her stories are the stories she has been told and retold throughout her life and the question of their validity is not as important to Kingston as the act of recording the ‘talk-stories’.

Similarly, William Butler Yeats, the famous Irish poet, perfected this form of creating a talk-story, a myth of one’s people. He dedicated his life’s work to creating a new ‘myth’ for his people by recording in his poems the history of the Irish people. Yeats says of the great writers, “…they tried to speak out of a people to a people, behind them stretched the generations” (Yeats, 1997, p. 405) and “Behind all Irish history hangs a great tapestry…” (Yeats, 1997, p. 407). It is within this tapestry that Yeats finds the substance of his own autobiographies and his myths. Many critics would question the autobiographical nature of Yeats works; one could call them biographical instead of autobiographical. Yet Yeats would counter that he has put his own history into every poem, his myths, his talk-stories are a part of the great tapestry.

Selective Memory

All versions of a life are true. All versions of a life are fiction.

The key is determining the time in which the story is being told. Is the meaning of the text created by the reader? Should the reader be responsible for validating the text when the experience was not theirs to begin with? In Narrative Means to Therapeutic Ends, psychologists Michael White and David Epston say, “Since we cannot know objective reality, all knowing requires an act of interpretation” (White and Epston, 1990, p. 2). Therefore, the autobiographical text, as well as any other text, is open to the interpretation of the reader.

Van de Pol (2013) reminds us that we recount memories that have been recounted many times over the years. Each story of a person’s life is “re-remembered” every time that they retell it. Again, the retelling depends on the stage of life the storyteller is in at any given point in time. Van de Pol contends that people who write autobiographies and memoirs are unreliable narrators, with memoir and personal history coming closer to the truth as it tends to reside more in relation to other people’s lives than just the recounting of the author’s life as autobiographies do (van de Pol, 2013).

Each story of a person’s life is “re-remembered” every time that they retell it.

It’s Your Story

David Carr, investigative reporter, says, “People remember what they can live with more often than how they lived.” (Hodes, 2022). How memory functions become problematic only when the author cannot or will not admit that their memory of an event is their memory. We all have had the experience of recounting a memory of our childhood and a parent or sibling will step in and say, “It didn’t happen that way! This is how I remember it….”. So, the writer of a memoir needs to recognize that their memory may not match someone else who also experienced the event. But then memoir is about one person’s life written by that one person, so their account does not make the recounting less true; it is simply their memory.

Think Like a Historian

In Notes from the Underground, Fydor Dostoyevsky says “…a true autobiography is almost an impossibility, and that man is bound to lie about himself”. Memory is selective and changes over time. It is not possible to use feelings of certitude as a means of determining truth. Yet, it is possible to hold as close to the truth as possible. In autobiographical writing, the writer must think like a historian. In a survey of Canadian students, Duncan Koerber found that many students were aware of selective memory and used other means of research to back up their own memory of an event; they thought like a historian and found other sources to verify that their recollection was accurate (Koerber, 2013, p. 59).

It is possible to hold as close to the truth as possible. In autobiographical writing, the writer must think like a historian.

Narrative Storytelling

In Maya Angelou’s novel, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, one reviewer comments that the story “…denies the form and its history, creating from each ending a new beginning, relocating the center to some luminous place in a volume yet to be” (Braxton, 1999, p. 130). Angelou records experience not as history, but as experience that she recognizes as changing in time.

Angelou epitomizes the statement that James Olney makes when he says,

“… even as the autobiographer fixes limits in the past, a new experiment in living, a new experience in consciousness … and a new projection or metaphor of a new self is under way”

(Olney, 1972).

Bennett and Royle state that “…the intractable problem of how to end an autobiography (is that) such a text can never catch up with itself because it takes longer to write about life than it takes to live it. In this sense, autobiography can never end” (Bennett & Royle, 1999). In this sense, the autobiography can also be said to never begin.

The autobiographical text is constantly shifting through time, moving from truth to fiction and back again to truth. The story has multiple beginnings as well as endings.

Angelou’s narrative has all the key elements of an autobiography except perhaps an ending. Her autobiographies tend to leave the reader hanging in the wind, wondering what comes next. It is perhaps fitting that Angelou’s books contain this element of serial novels. It is through the serial autobiography that autobiography approaches its true and ultimate form – an account through time of a person’s life, a story with many beginnings that does not end until the author himself reaches the end. And even then, the story continues, doesn’t it?

Getting past the problem of truth

Autobiographical writing, in whichever form the writer chooses, contributes to the preservation of history and adds new perspectives to historical periods. Recounting events, thoughts, and feelings require all the elements of a narrative, and writers adhere to the storytelling techniques that are crucial to narrative writing (Lawrence, 2013). The writing of personal narrative is inherently a subjective experience, so it is therefore subject to becoming too dependent on opinion.

Writers need to tell the story in such a way that the narrative takes in the perspectives of others experiencing the personal event as well. This type of attention helps in eliminating bias and bringing validity to the author’s voice.

Universal patterns

We can provide validity to our authorial voice by using the storytelling format that we all have been surrounded with our entire lives. The plotline, the dialogue, the dramatic struggles, and the conflicts and triumphs are all things that humans are intimately familiar with (Gulwani, et al., 2022). As our personal histories take shape as talk-stories, we touch the hearts of our readers because our lives are similar to theirs.

https://www.slideserve.com/mercedes-douglas/archetypes-journey-of-the-hero

The inherent patterns of our lives are universal, and it is these patterns that give the autobiographical writer validity. You have a story, many stories, to tell. So, go tell your story.

- Use ‘talk-story’

- Contribute to the ‘tapestry’ of history

- Think like a historian

- Use the story format

- Tap into the universal patterns

=========================================================

References

Bennett, Andrew and Nicholas Royle. (1999). Introduction to literature, criticism and theory. 2nd Edition. Prentice Hall.

Braxton, Joanne, ed. (1999). I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings: a casebook. Oxford University Press.

de Bres, Helena (2021). Artful Truths: The Philosophy of Memoir. Publishers Weekly, 268(21), 73. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226793948.003.0001

Dostoyevsky, Fydor. Notes from the Underground.

Gulwani, S., Barik, T., & Juarez, M. (2022). Storytelling and Science: Incorporating storytelling into organizational culture. Communications of the ACM, 65(10), 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1145/3526100

Hamilton, Karen (2019). Lostmans heritage: pioneers in the Florida Everglades. Yesterday Press.

Hodes, M. (2022). As If I Wasn’t There: Writing from a Child’s Memory. American Historical Review, 127(2), 913–922. https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/rhac158

Karalis Noel, T., Minematsu, A., & Bosca, N. (2023). Collective Autoethnography as a Transformative Narrative Methodology. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069231203944

Lawrence, H. (2013). Personal, reflective writing: A pedagogical strategy for teaching business students to write. Business Communication Quarterly, 76(2), 192–206.

Novick, Peter. (1988). That Noble Dream: The ‘Objectivity Question’ and the American Historical Profession. Cambridge University Press.

Kingston, Maxine Hong (2001). No Name Woman. The Longman anthology of women’s literature.

Koerber, D. (2013). Truth, Memory, Selectivity: Understanding Historical Work by Writing Personal Histories. Composition Studies, 41(1), 51–69. https://research.ebsco.com/c/36ffkw/viewer/pdf/vdhetodwfj

OED, Oxford English Dictionary, (2023). https://www.oed.com/

Olney, James (1972). Metaphors of self: the meaning of autobiography. Princeton University Press.

Starobinski, Jean (1990). “The Style of Autobiography,” Autobiography: essays theoretical and critical. ed. Princeton University Press.

Underkofler, M., Rossi, S., & Korbal, E. (2020). Using Storytelling to Teach Effective Followership. New Directions for Student Leadership, 2020(167), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.20400

van de Pol, Caroline, Truth in memoir, thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2013. https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/4009

White, Michael and David Epston (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. WW Norton & Company.

Wong, Sau-ling Cynthia (1999). “Autobiography as Guided Chinatown Tour?: Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior and the Chinese American Autobiography Controversy”. Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior: a casebook. Ed., 29-53.

Yeats, William Butler (1997). The Yeats reader: a portable compendium of poetry, drama, and prose. Richard Finneran, Ed. Scribner Poetry.