Autobiographical writing is inherently the truth. Your truth. That is an important distinction.

We all remember things differently. Your sister will likely remember events in a different way than you, for example. In addition, what you think about your life today may not be what you think about it twenty years from now. This is the problem with autobiography – it is subjective to time, forever changing depending on the moment it is written down.

PHOTO CREDIT: Handling the Truth by Beth Kephart

If you approach the writing worrying about who you might upset, you won’t get much writing completed. You must convince your brain that you are allowed to tell your story the way you remember it.

An autobiography or memoir tells the truth where the truth matters. You won’t change the date of the hurricane that slammed through your town or alter the name of the famous politician you met one year who gave you great advice. You get the point. Your readers expect the truth.

You will also tell the truth, to the best of your ability, about your feelings and perceptions of an event. Again, the reader expects the truth.

I remember reading my father’s autobiography and becoming upset when he wrote about my birth. “Karen was born and all went well.” That was it. No more, no less. My mother had a terrible pregnancy with me and a dangerous, challenging birth experience. I was born very ill and was whisked away from her and placed in isolation for two weeks. I came very close to death. But according to my father, “…all went well.”

Looking back, I can put the incident into context. My father was married with two toddlers, working several part time jobs while he attended full time at the university. We lived in family housing on campus. He brought his mother up from Key West to Gainesville to help my mother. It was 1962. He did what men did back then; he took care of his family and left emotion out of it. What did he feel about the chaos surrounding my birth? We will never know. He simply does not remember any of it.

You too will encounter this issue. Friends and family will say, “It didn’t happen like that!” Remember, these are your memories, not theirs.

Including a Disclaimer

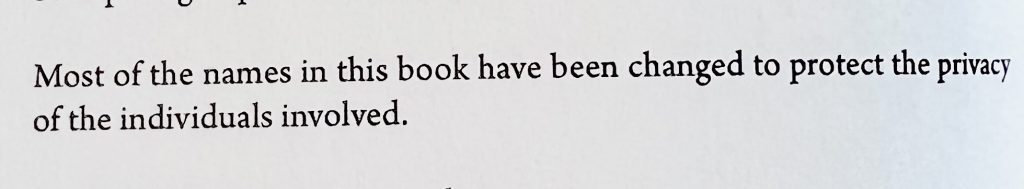

One way to deal with the subjectivity of memory is to add a disclaimer to the front pages of your work.

In The New Life Story, Tristine Rainer suggests that you write your disclaimer first, before you begin writing your story. Doing so will give you permission to write honestly and creatively. You can always change it later. Or get rid of it all together.

It is helpful to use your very first exercise about why you are writing your memoir to help you form your disclaimer.

A few examples from Rainer:

**Where I have been unable to remember fully, I have allowed my imagination to fill in.

**To protect the privacy of certain individuals I have in many ways disguised their identities.

**Sometimes I have taken poetic license with the order of events for the sake of the narrative.

In The Brooklyn Hobo, the author, Alexander Procho, added a disclaimer. Sometimes memoirs take a turn into the fictional realm. As he recounts stories about tripping on LSD or a bipolar incident, his words and thoughts transform into distinct fabrications, not by conscious choice, but simply because he is recording dream-like states.

Brooklyn Hobo Disclaimer: Some names have been changed to protect identities and some characters are entirely fictional. All of the contents herein are based on memory – subjective memory. Therefore, the stories found on these pages, while based on real happenings, are subject to the tricky minefields of memory and cannot and should not be construed as fact.

Here are a few other examples of disclaimers:

To the Reader: Lord knows I’ve tried my best to tell the truth here, even when it would have been simpler to fabricate. While all of the incidents in this essay collection happened, I have changed the names of people, businesses, and institutions when it felt right. In a few cases I even nudged a fact slightly, but no more than necessary and only to avoid identifying somebody I love. I’m writing from memory most of the time, so be forgiving, gentle reader. I went to college in the seventies.”

Melissa Delbridge, Family Bible

Disclaimer: The author acknowledges that he is not Bob Woodward. Mr. Woodward is scrupulous with names and dates. This author is not. Mr. Woodward would never suggest that something happened in October when, in fact, it occurred in April. This author would. Mr. Woodward recounts conversations as they actually occurred. This author would like to do that, but alas, he does not excel at penmanship and he cannot read his notes. However, the author has an excellent memory. You can trust him. J. Maarten Troost, Getting Stoned with Savages

The tales you are about to read are the truth, practically the truth, and nothing less than a half-truth… Nick Trout, Tell Me Where it Hurts: A Day of Humor, Healing and Hope in My Life as an Animal Surgeon

Quotes on Truth in Writing

… if you treat them with complexity and compassion, sometimes they will feel as though they’ve been honored, not because they’re presented in some ideal way but because they’re presented with understanding.

Kim Barnes author of In The Wilderness and Hungry for the World

…yours is not the only story for perspective on family or on your community, but it is a perfectly valid voice among the chorus.

Tell It Slant by Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola

I will say with memoir, you must be honest. You must be truthful.

–Elie Wiesel, author of Night

Tell the story of the mountain you climbed. Your words could become a page in some else’s survival guide.

–Morgan Harper Nichols, poet and artist

Isn’t telling about something—using words, English or Japanese—already something of an invention? Isn’t just looking upon this world already something of an invention?

Yann Martel, The Life of Pi

But the kind of judgment necessary to the good personal essay, or to the memoir, is not that nasty tendency to oversimplify and dismiss other people out of hand but rather the willingness to form and express complex opinions, both positive and negative.

– Judith Barrington, Writing the Memoir